Many software systems use a batch-driven process to operate. They accumulate data in a database and periodically a job will process the data to produce some result. In the past, this was sufficient. However, modern systems need to respond faster. They may not be able to wait for a batch to start. Many systems have turned to an Event-Driven approach because it is capable of reacting to events as they happen. However, despite the power of these systems, they do introduce new challenges.

How to handle duplicate events

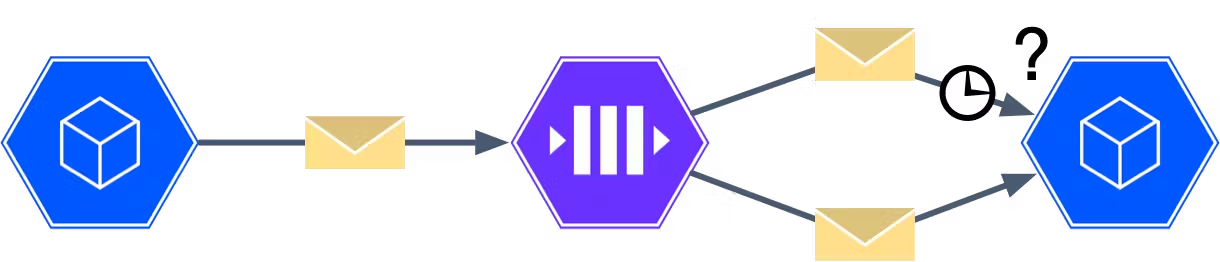

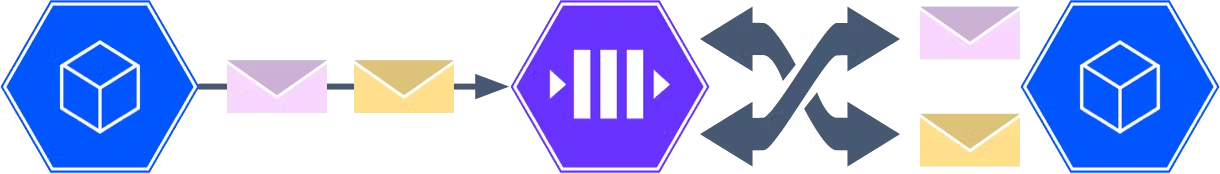

Events are usually sent with an at-least-once delivery guarantee. This means that each event is guaranteed to reach its destination. However, it is possible that some events may need to be delivered more than once. For example, if a timeout occurs when we are attempting to deliver an event, we have no way of knowing if that event was received or not. In this case, we redeliver the event to ensure that it makes it to the destination, at the risk of creating a duplicate.

Because of the at-least-once delivery guarantee, our downstream systems need a way to handle potential duplicates. This is where we rely on a property known as idempotency.

What is Idempotency?

Idempotency is a property of an operation that allows it to be applied multiple times without changing the result.

Our goal is to create events that are either naturally idempotent, or if necessary, introduce additional data into the event in order to make it idempotent.

We can see idempotency in action by looking at some basic data structures. Adding an item to a set is a naturally idempotent operation. Suppose we take a set of numbers such as (1,3,6) and we try to add the number 4 to the set. That will result in (1,3,4,6). One property of a set is that it doesn’t allow for duplicates. This means that no matter how many times we add the number 4, we always end up with (1,3,4,6). This is different from a list which can contain duplicates. If this was a list, then adding 4 twice would give us (1,3,4,4,6). Here, we have an operation that is not naturally idempotent.

Let’s look at a more complex example. At a bank, certain operations will be naturally idempotent, while others might have to be modified. For example, updating account information such as names, phone numbers etc. is naturally idempotent. If I want to set the phone number for the account to 555-1234, I can apply that operation as many times as I want, and the result will always be the same.

RELATED

Data Mesh: How Netflix moves and processes data from CockroachDB

But what about transactions on the account? Are they naturally idempotent?

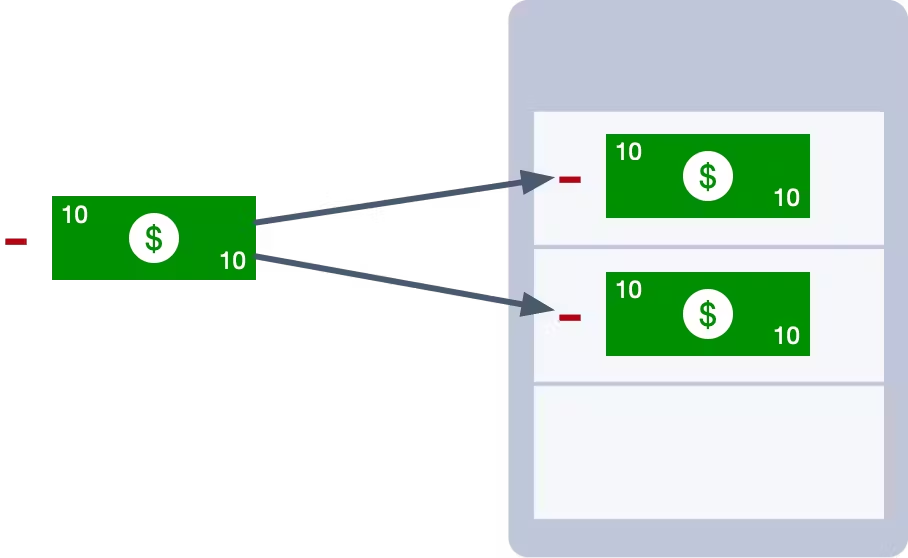

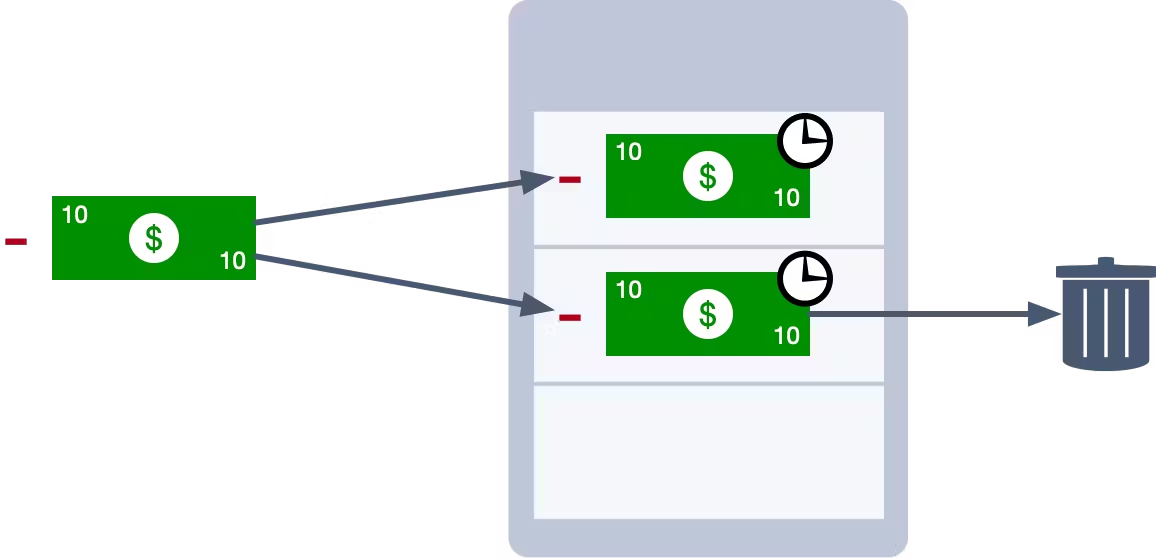

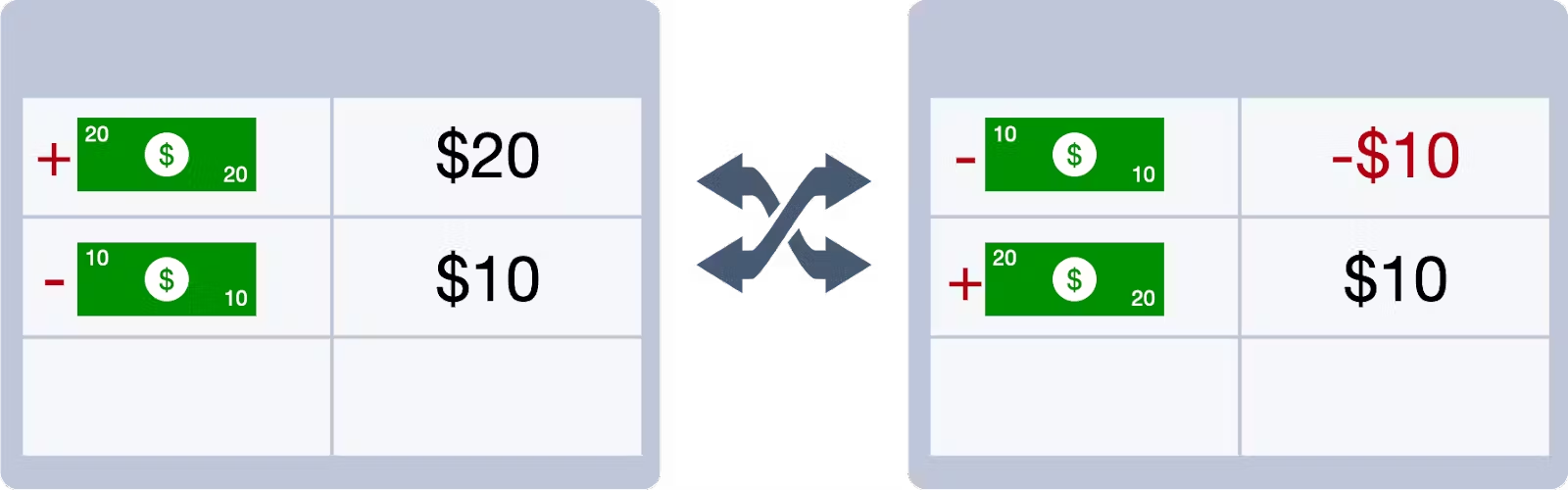

A withdrawal on an account is not a naturally idempotent operation. If we withdraw $10 from our account, and then apply the same operation a second time, we will have withdrawn $20. This means if we get a duplicate of a withdrawal event, we could potentially introduce an error into the system. That will result in very frustrated account holders, especially if this happens frequently.

So how can we make a withdrawal idempotent?

A naive approach would be to simply look at the timestamps of the transaction. If we find two transactions with the same timestamp, then we assume that one is a duplicate, and we discard it. For some systems, this might be sufficient. However, in highly concurrent systems, it is fairly common to find duplicate timestamps and this technique would be unreliable. For a banking system, we need to be confident.

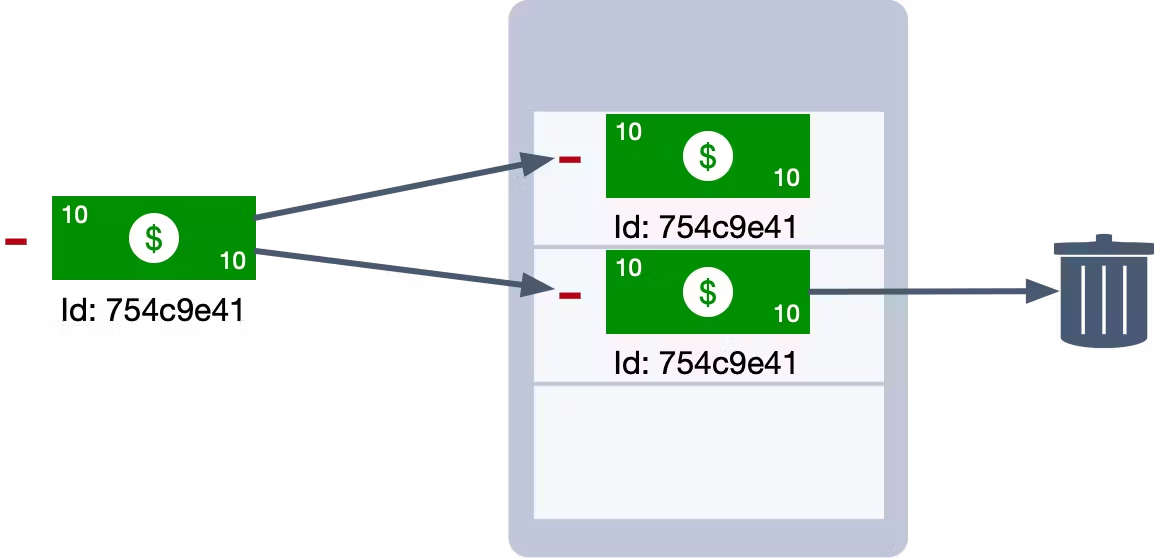

Instead, we could use a transaction Id. Each transaction is assigned a unique identifier when it is created. We can use this identifier to enforce idempotency. Each time we apply a transaction, we check the database to see if another transaction with the same Id already exists. If it does, then we know we have found a duplicate and we can safely ignore it.

This is fairly easy to implement in CockroachDB. When you handle an event, you can extract the Id from that event. If you use this Id as the primary key in your table, then if you try to insert the same Id twice (i.e. you process the same event twice), it will fail due to a duplicate key exception. When the failure occurs, you know you have encountered a duplicate.

Unique Identifiers can be applied in many situations. But in order to use them, we need a reliable technique for generating Ids.

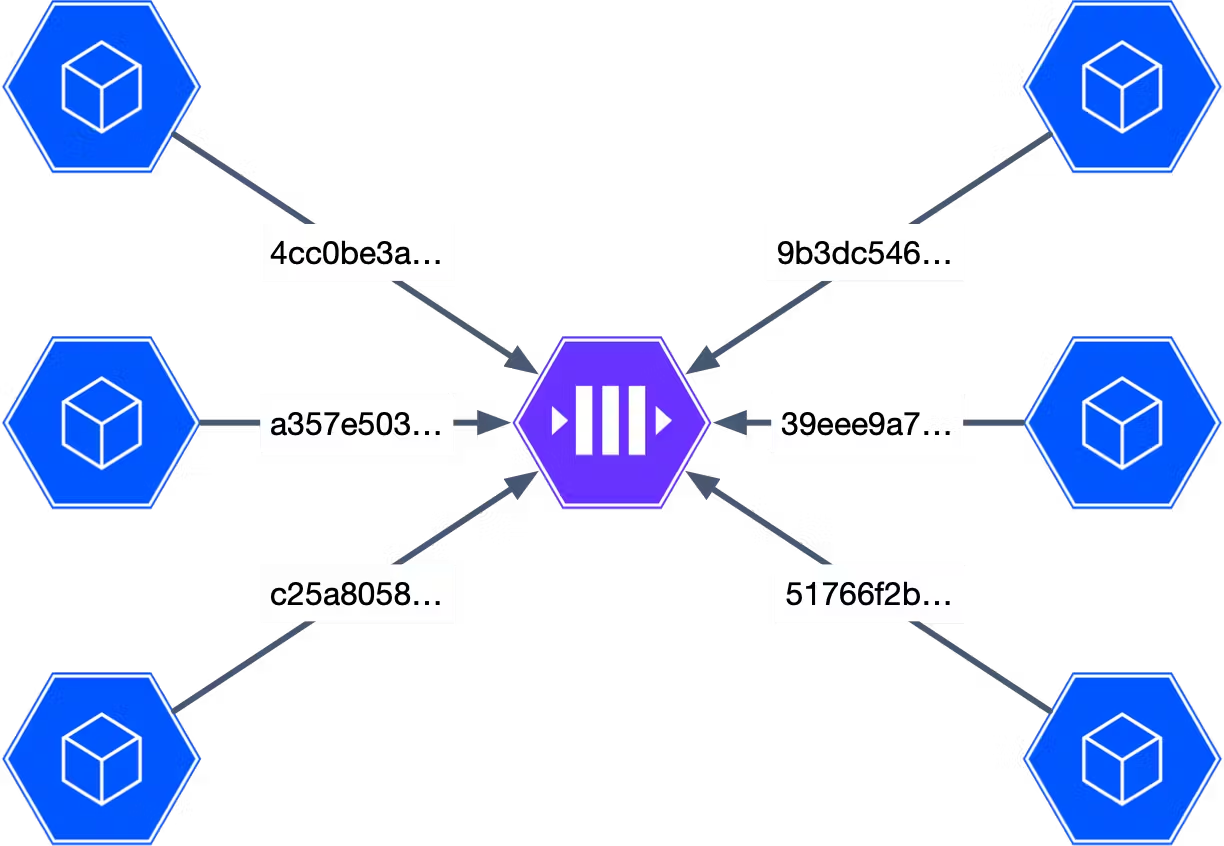

A popular approach is to use a monotonically increasing number. Each number is higher than the previous one, and we can guarantee that we will never encounter a duplicate as long as we don’t run out of numbers. However, this approach requires a centralized service to keep track of the current number and assign the next one. This creates a bottleneck in the system. Every new Id has to be assigned by a single source of truth. When you try to scale up, the approach might crumble under the weight of too many events. For this reason, it is not recommended in highly distributed and scalable applications.

A better option is to use an identifier such as a UUID. When created with a high degree of entropy, UUIDs are guaranteed to be more or less unique (If you create many trillions of IDs in a year, you might encounter a collision). CockroachDB includes facilities for generating UUIDs with the necessary entropy. Combined with the distributed nature of the database, it allows us to use these Ids to avoid duplication and eliminate the central bottleneck.

A third option is to generate a unique Id from the data in the event. In our banking example, we might be able to use a combination of timestamps, account Ids, and device Ids to create an identifier that is guaranteed to be unique across all transactions. Where a naturally unique identifier is available, it is generally preferred. However, sometimes we need to avoid identifiers that contain sensitive data, in which case, this approach might not work.

Whatever approach you decide to use, the idea is to embed that unique identifier into your events so that downstream systems can use them to deduplicate as required.

How to handle out of order events

Another issue that can occur in Event-Driven systems is out-of-order events. Here, the challenge is related to the costs associated with absolute ordering. If we want to guarantee that all events are applied in an absolute order then we must ensure that they are created and consumed inside of single-threaded processes. If we introduce any concurrency into either the source or destination of the events, it could result in them being processed in a non-deterministic order.

However, restricting the system to a single-threaded operation means that we can not scale. We have created a severe bottleneck and there is no effective way to avoid it.

Therefore, when we build event-driven systems, we want to avoid total ordering of events wherever possible. Instead, we look for opportunities to have events that can be handled unordered, or where we can limit the scope of the ordering.

Going back to our banking example, if we start with a bank account balance of $0, then deposit $20, then withdraw $10, we end up with a final balance of $10. No matter what order we apply those transactions, we’ll always end up with the same result.

But, the details are important. Because although the final balance is always the same, if we apply the transactions out of order, we will temporarily have a negative balance.

So how do we handle this?

Well, a simple option is just to say it’s okay to have a negative balance. This is basically how an overdraft works. As long as the negative balance is for a very short period of time, we could assume it is just a temporary system issue and not bother charging the user an overdraft fee. If it turns out to last longer, then it is more likely a user issue and we can charge a fee.

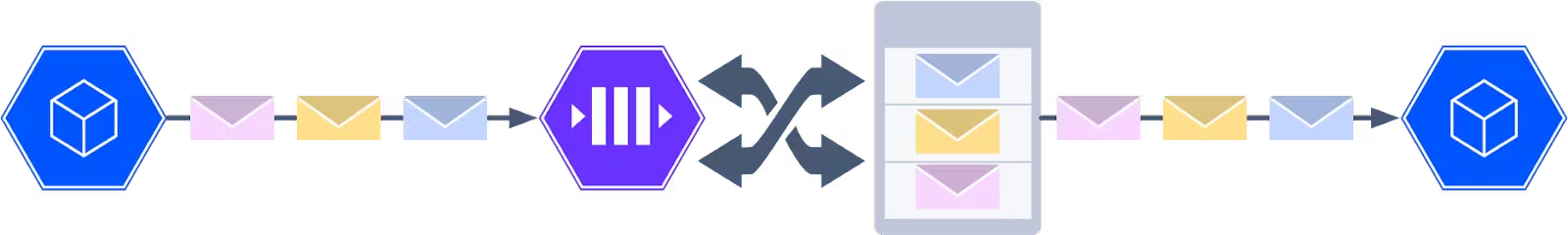

An alternative approach is to use some of the techniques we discussed when talking about idempotency. We can use these techniques to buffer and sort events as they are received in order to fix the ordering. Then we periodically flush the buffer. However, this kind of ordering does re-introduce a batch process, although the batch might be kept relatively small.

An automatically incrementing id can provide us with an absolute order of events so that we can sort them as required, but it does re-introduce the problem of a single bottleneck for managing those ids.

Timestamps can also be used, although in this case, the order isn’t guaranteed to be absolute. Multiple events may occur at the same time. In addition, we can’t always promise that the clocks will be synchronized. In this case, we have to assume there might be some short period of time where we have no guarantee of order and events may be applied in a semi-random fashion. We can eliminate some of the uncertainty by letting CockroachDB manage the timestamps. It uses sophisticated techniques to keep the system clocks in sync.

RELATED

Message queuing and the database: Solving the dual write problem

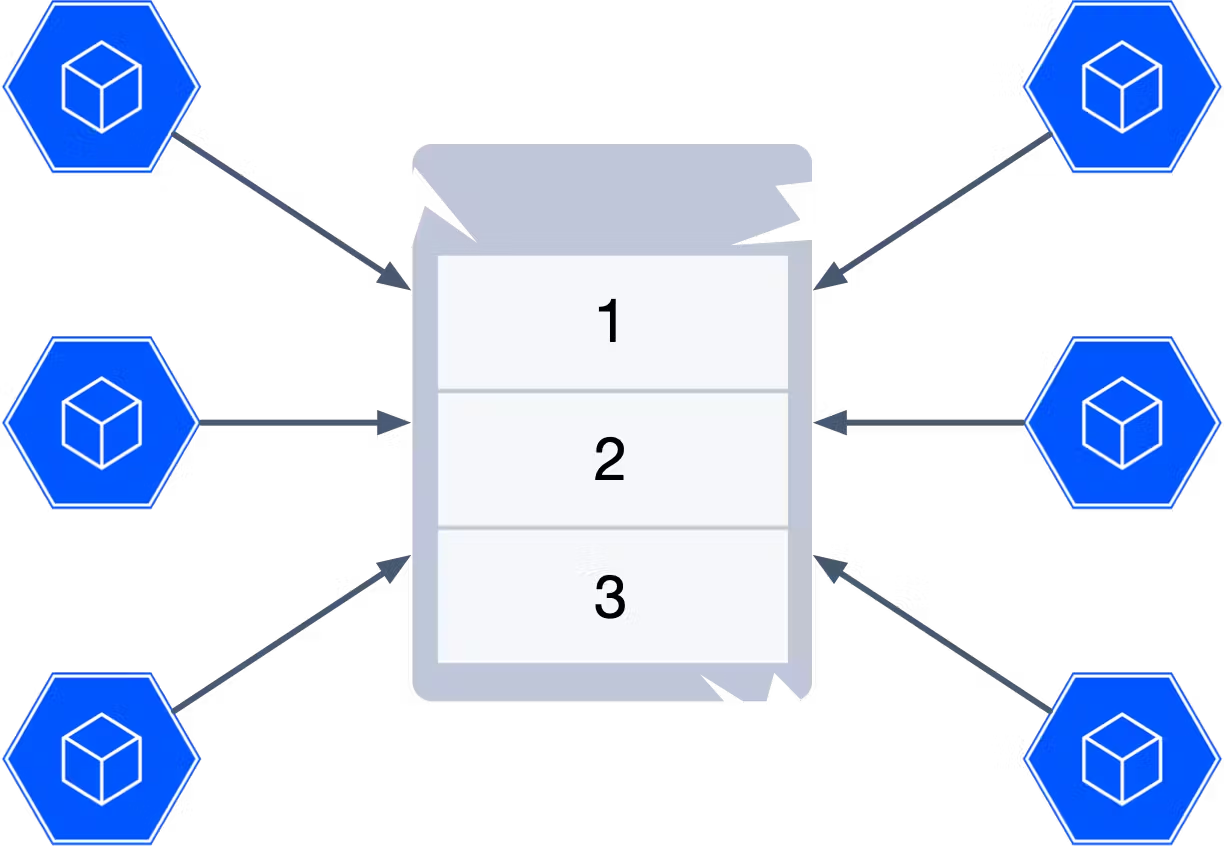

A common approach to reducing some of the problems with using timestamps or numeric ids is to limit the scope. In this case, we don’t try to apply an absolute order to all events. And we don’t try to guarantee uniqueness of Ids across all events. Instead, we reduce the scope of the ordering and uniqueness using some other data we have access to.

For example, in a bank if we applied total ordering to all events, it would impact every account at the bank. But we don’t really need that. All that matters is that the transaction order is applied within a specific account Id. In this case, we can take all of the transactions for that specific account, and properly order them. By limiting the scope, we reduce the size of the batches we need to process, decrease the likelihood of conflicts, and allow for better scalability. Using a single account Id means that we can process multiple accounts in parallel. This eliminates many of the bottlenecks we would otherwise encounter.

These approaches can help us when ordering is important. However, the single best solution is to avoid the requirement to begin with. An unordered handling of events is the most scalable option we have available.

Learn more about event-driven architecture

Event-Driven architectures are powerful, but they do introduce some new challenges. The important thing to understand is that there is no universal solution to these problems. Instead, we need to recognize that each potential solution has its advantages. It is our job to understand the possibilities and apply the one that best fits our use case.

In the past, we’ve published useful blogs and videos about event-driven architecture concepts like when to use Change Data Capture or how to finetune changefeeds for performance and durability. Those are both good resources. But for a thorough understanding of event-driven architecture I have to recommend the course that I wrote for Cockroach University. Check it out! And here’s an example of the kind of instruction you can expect from the course: